Recently we have expanded the Bertha M. Ingle website (

berthamayingle.ca ) in several ways, one significant addition being a list and descriptions of all the known exhibitions of her work. These span well over a century, from 1895 to 2019.

For most of the known exhibitions that took place during her lifetime (1878-1962), we have authoritative documentation of the dates, the locations, and in most cases the titles of the works exhibited – but usually no certain knowledge of what those works looked like. An exception to that final omission is the Perkins Bull Collection, first exhibited in 1934; happily we do have photographs of the two Ingle works therein, one because a photo of the painting was reproduced in the published catalogue (and Bertha kept her own print of the photo), and the other because that painting itself is now part of the art collection at Victoria University in the University of Toronto, and is on display in the Offices of the Principal.

|

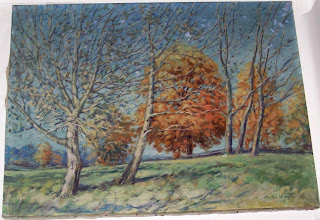

| Bertha M. Ingle: Autumn Leaves |

|

| Bertha M. Ingle: Autumn Sunlight, Churchville |

A more surprising exception to the rule is an exhibition that was almost certainly the last one mounted (or was at least planned) during her lifetime, in the late 1950s. For that one, we have no documentation at all regarding location or exact date, only our own faintly remembered family oral history. Yet, perhaps paradoxically, the nature and the appearance of most of the works that were included are known in detail and with a high degree of certainty.

The evidence for that knowledge has been hiding in plain sight for many years, but has only recently been brought into focus. Among the many works we have inherited from Bertha’s estate are sixteen portraits in oils that all share certain characteristics. Their commonality was not obvious when we first began to photograph and catalogue the works, largely because they were not all stored together and because we were working our way through boxes and bags of works that had previously been sorted by size or by other unknown criteria. But the recent realization of their commonality leads us pretty much inescapably to the conclusion that they were intended to be exhibited together – along with a few more portraits that we don’t have.

The discovery came about as part of our ongoing effort to have our Ingle oil paintings cleaned and repaired as necessary. That effort began (and continues) with those works most in need of conservation, but we have also found that even works that came to us in presentable condition have benefitted greatly from simple cleaning and revarnishing, bringing once again into view the original true colours that are such a hallmark of Ingle’s work.

Recently we selected for conservation three portraits in oils that had been varnished with such a high gloss that photographing them accurately had been a challenge, and lighting them without creating reflected glare was difficult. We asked conservator and artist Guennadi Kalinine (of Dundas, Ontario,

gkstudio.ca ) to do a basic cleaning and re-varnishing with a less glossy archival varnish.

It struck me, then, that I knew of a few other oil paintings where the varnish is similarly glossy, so I set out to determine how many others we might also be sending Guennadi’s way if the results are as satisfying as we anticipate they will be. After finding several such works, I suddenly realized that there was a sub-group of them for which the glossy varnish was not the only thing they had in common.

I eventually found sixteen oil paintings that were undeniably a well-defined set. They were all portraits; all painted on canvas; all mounted (by adhesive) onto masonite; all signed with exactly the same signature style (in block capitals); and all varnished after they had been mounted on the masonite. And here’s the clincher: each had a unique number, roughly scrawled on the verso of the masonite in red pencil or crayon, the numbers ranging between 1 and 20. The penny dropped at last!

Here are three of the portraits:

There is one further common characteristic of these portraits that deserves mention. The signatures vary noticeably in the spacing between 'BERTHA' and 'M. INGLE'. That variation is most unusual, not generally found in other paintings that Bertha signed in block capitals. Looking carefully at all sixteen portraits, I have come to believe that the explanation is simple yet surprising: I believe she initially signed all the works as 'M. INGLE', and added 'BERTHA' afterwards. One painting is in a circular field, and 'M. INGLE' is perfectly centred at the bottom of the circle, an especially telling bit of evidence.

Choosing 'M. INGLE' may have been an attempt to conceal the fact that she was a woman, mindful of the bias common at that time against women artists, in Canada (and elsewhere). In earlier years she had used a made-up name, 'Maylaw', to sign a few paintings, possibly for a similar reason. We also suspect that 'Bertha' was not a name she greatly loved; although she almost always used it as part of her professional name, she preferred for informal purposes to be called 'Bert' or 'Bertie', from quite a young age.

However, she changed her mind, I believe, and added 'BERTHA' after all. Adding that name, writing it from left to right, would account for the variation of spacing we observe – and also for slight differences in the size or alignment of the letters in some instances. How I wish we had been let into the discussion at the time!

From our memory of those days, we believe the exhibition may have been planned for Eaton’s College Street in Toronto, where there was a thriving commercial Fine Arts gallery, as well as the famous Grand Foyer adjoining the Eaton Auditorium on the seventh floor. To me there can be little doubt that an exhibition did take place somewhere, mainly because we have only sixteen out of (at least) twenty. That suggests that some may have been sold or given as gifts as a result of the exhibition.

Please contact us if you have any of them! You can see images of all the paintings we have in an album found

HERE .

Bertha also left us several bound sketchbooks, including one which has many references to Québec and must have been her constant companion during her time there. The second page has a rough pencil sketch of a horse and cart which appears to have been a preliminary study for the oil painting – same position, same angle.

Bertha also left us several bound sketchbooks, including one which has many references to Québec and must have been her constant companion during her time there. The second page has a rough pencil sketch of a horse and cart which appears to have been a preliminary study for the oil painting – same position, same angle.

Taken all together, these clues strongly suggest that the oil painting, along with Bertha’s smaller watercolour version of the same scene, are indeed depictions of the rue du Petit-Champlain.

Taken all together, these clues strongly suggest that the oil painting, along with Bertha’s smaller watercolour version of the same scene, are indeed depictions of the rue du Petit-Champlain.